The Ionesco show

The story

The beginning of The Bald Soprano

In the backroom of a café on the boulevard Saint-Michel a group of actors seated around a table roar with laughter. Nicholas Bataille, a young director, reads aloud the first scenes of a play by the young playwright Eugene Ionesco.

A couple that has nothing left to say to say to each other after twenty years of marriage spends the evening with another couple that no longer recognize each other.

The text has already been submitted to Bernard Grasset who thinks it is no good and has been refused by the Comédie Française. These first scenes were drafted by Ionesco after trying to learn English from the Assimil method called English without toil. In the readymade phrases aligned one after the other he saw an inconsistency in language which became the inspiration for his play. From the beginning this admirer of Lewis Carroll and other surrealists knew he wanted to make his play a parody of theatre.

Nicolas Bataille sets the pages back on the table. All at once Simone Mozet, Odette Barrois, Paulette Frantz, and Claude Mansard cry out,

"We have to do it!»

«But it’s too short…»someone says.

«It needs a new title»,

declares another.

Nicolas Bataille quickly arranges a meeting with Ionesco.

«I want to stage your play.»

«Really? Are you out of your mind? Everyone has told me it’s impossible to perform.»

«We want to do it."

Rehearsals last nearly five months. One day, a stockbroker acquainted with Ionesco invites the troupe to perform the play in the sitting room of his Parisian townhouse near the Champ-de-Mars. They perform the play as a comedy. The presentation is an immense disappointment to the audience as well as the actors. “Why doesn’t it work?” the young director asks himself. His partner Akakia Viala suggests that instead, they play against the text and perform it dramatically. Bataille takes this idea and improves on it. The senseless text performed solemnly and ceremoniously becomes compelling. Filled with references to Jules Verne, Bataille found unsettling similarities in the language and attitudes of the novelist’s and the playwright’s characters. Ionesco attends all the rehearsals and with the troupe he thinks on a new title for his play. It comes from a slip of the tongue of the actor Jacques-Henri Huet playing the pompous fireman. During his Rhume monologue he replaces the ‘blonde schoolteacher’ with a ‘bald soprano’. When Ionesco hears this he jumps out of his seat and declares, “That’s it!”

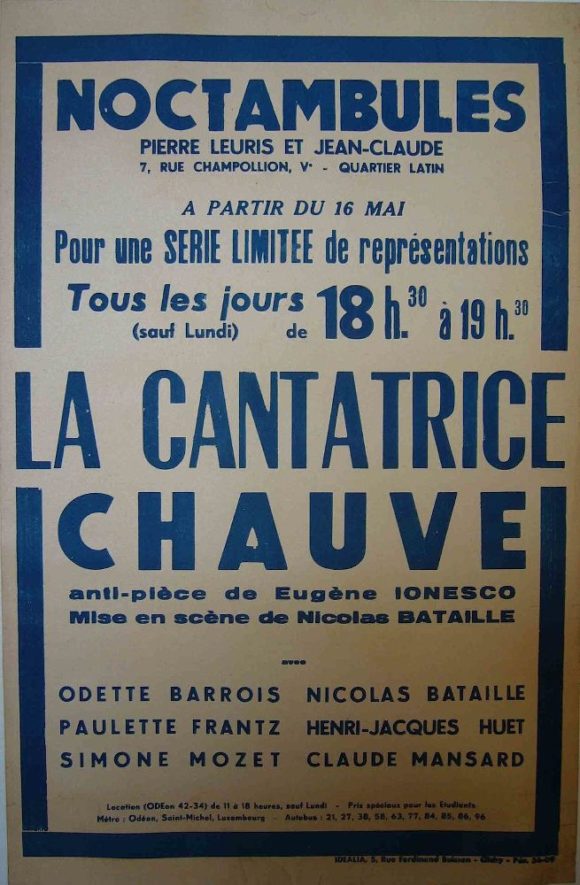

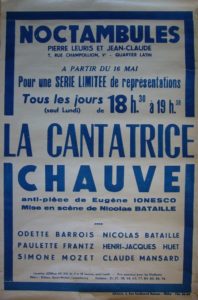

The troupe obtains an audition at the Theatre des Noctambules. Managed since 1939 by a pair of theatre enthusiasts, Pierre Leuris and Jean Claude, this theatre became after a difficult beginning a Mecca for new, experimental genres of theatre.

"It’s marvellous, exclaims Pierre Leuris, the only problem is that it lasts only one hour! What do you expect me to do with one hour? Listen, I would like to put you in the schedule but at 6:00 pm. I have a show starting at 9:00 pm."

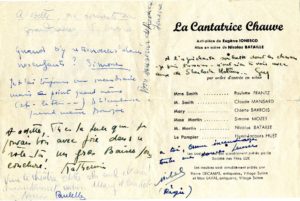

The time slot is mediocre but the troupe does not have a choice. Their scenery is made up of furniture borrowed from the actors’ parents and costumes borrowed from the film production of Occupe-toi d’Amelie (Keep an Eye on Amelie) directed by Claude Autant-Lara, a friend of Nicolas Bataille.

The play’s opening night is May 10, 1950 and the turnout is disappointing. Eugene Ionesco anxiously watches the performance in the wings. During the Smiths’ scene he hears laughter. “But…but they’re laughing,” he mummers to himself. It does not last.

The public’s reaction is mixed. Some even insult them, “Who are these fools! They’re mocking us!” However, intellectuals such as Camus, Breton, or Queneau are won over. The critics’ reviews are mixed as well. While some such as Jacques Lemarchand have only praise for the play others incinerate it without mercy. Jean-Baptiste Jeener will write, “Meanwhile the play is driving away the theatre’s audience.” The lack of an audience is what forces the play to close after only one month of performances.

A hard Lesson to learn

"I would like to put on one of your plays. Do you have anything new?"

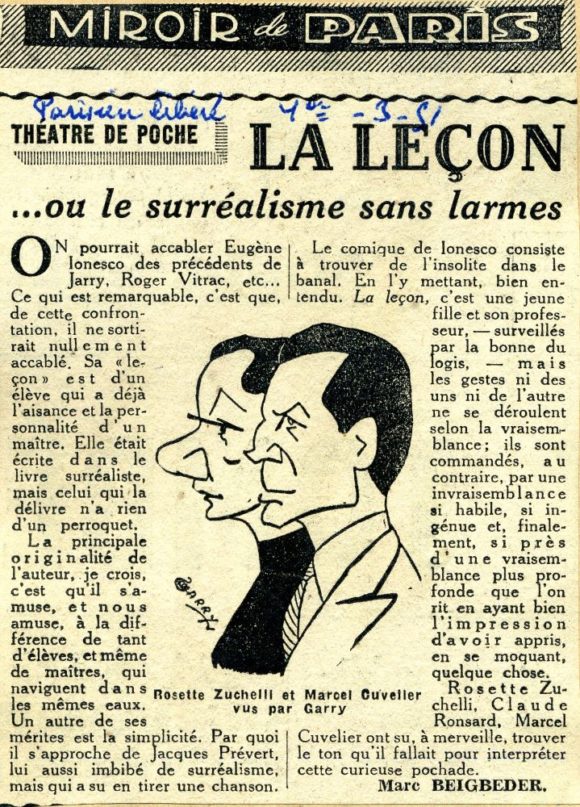

Marcel Cuvelier asks Eugene Ionesco one evening after a performance of La Cantatrice Chauve. Ionesco is surprised, it is the first time someone has asked him this question. “I am currently writing one,” the playwright answers. “It’s the story of a lesson, a professor and his pupil. At the end the professor kills the pupil.” The tale of little red riding hood devoured by the big bad wolf. In this allegory of the devastating effects of total dictatorial power, the comical absurdity quickly turns into a nightmare.

To stage a play by an unknown playwright with unknown actors and an unknown director they have to find a small theatre. Marcel Cuvelier contacts Corentin Quefellec, the manager of the Theatre de Poche. He reads the La Leçon but is unimpressed. However, one day he makes Cuvelier an offer, “I have nothing scheduled for the month of March, give me seventy thousand francs and the theatre is yours.” Cuvelier asks for three days to think it over. A grant is out of the question. “Stage the play first,” those around him say.

He makes a deal with the Egyptian actor Gamil Rhatib who is desperately trying to put on a short drama Les Assassins (The Assassins). Rhatib brings fifty thousand francs and in return his play is scheduled with La Leçon. But this alone is not enough.

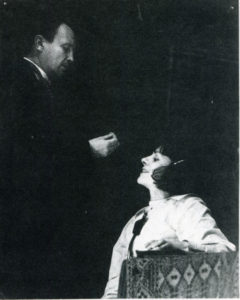

Marcel then calls an old friend; she and her sister quickly empty their bank accounts to make up the rest. There is not a penny for advertising, scenery, or costumes. This is of little importance. The director borrows the theatre’s grey curtains, uses a table and three chairs he finds there, and asks that each actor bring their own costume. Ionesco attends nearly every rehearsal. “To be honest, we put this play on together,” admits Macel Cuvelier. “And I was always up on the stage.”

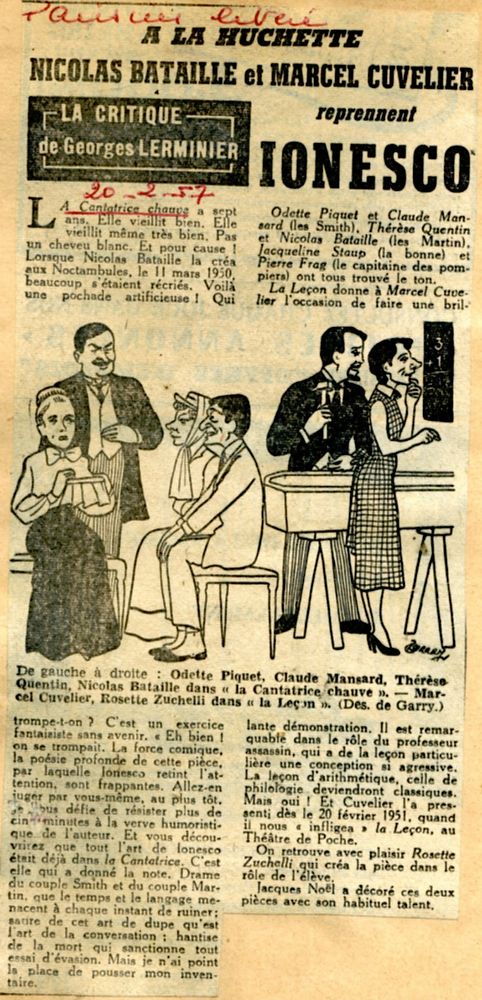

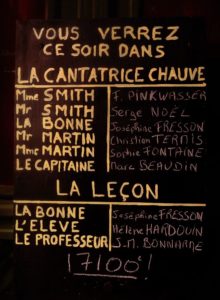

The play opens February 20, 1951 at the Theatre de Poche, with Marcel Cuvelier as the professor, Rosette Zucchelli as the pupil, and Claude Mansard as the maid. It receives the same reviews as Eugene Ionesco’s first play and closes just a quickly.

The first union

In the spring of 1952 Ionesco confirms his status as a dramaturge: Sylvain Dhomme stages Les Chaises (The Chairs) at the Theatre Lancry. The play’s scenery is designed by Jacques Noël and has a certain Tsilla Chelton in the lead. As usual, a triumphant opening night and an audience are both missing. The theatre then offers Marcel Cuvelier the opportunity to re-stage La Leçon. Once again, it is a failure.

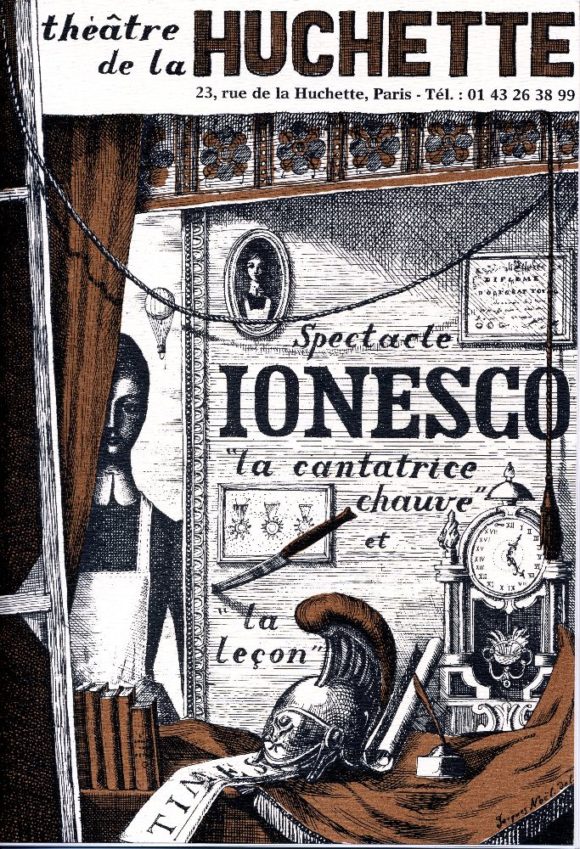

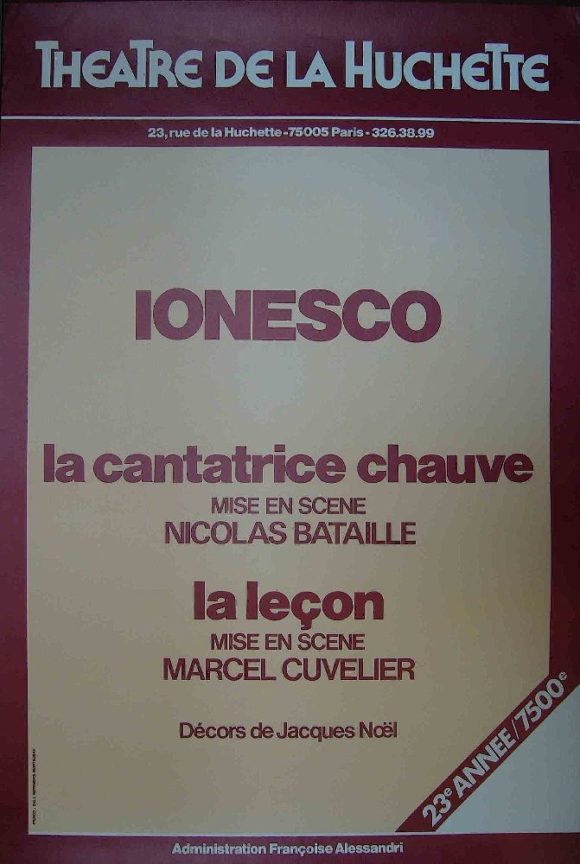

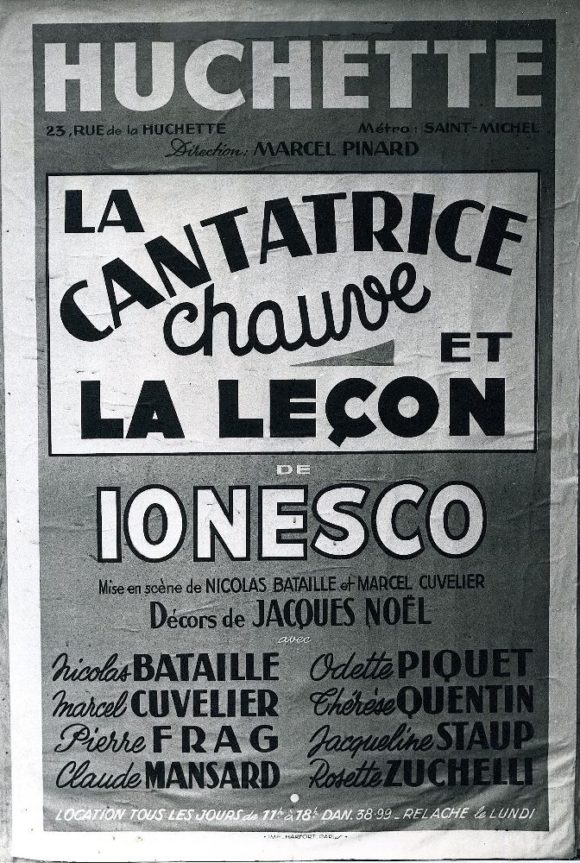

The director perseveres. Following the withdrawal of a play; the Théâtre de la Huchette, managed by Marcel Pinard, becomes free for three months. Cuvelier jumps at the opportunity. He recalls that a critic even once suggested that the La Cantatrice Chauve and La Leçon be performed together. Marcel Cuvelier quickly calls Nicolas Bataille who is ready and willing.

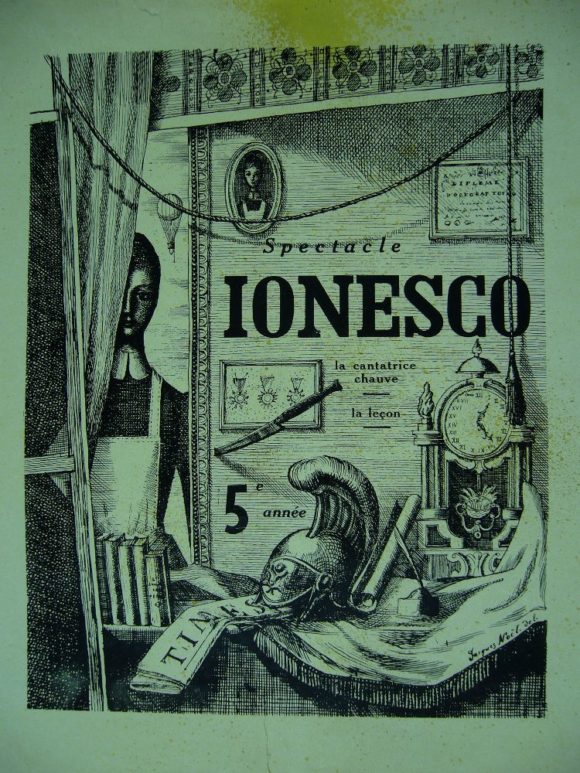

Ionesco appoints Jacques Noël as the set decorator. A quiet and clever young man, he presents the non-negligible advantage of working together. He uses partitions left behind by a previous production to produce a reversible set. One side is painted green (a taboo colour in the Théâtre but, Nicolas Bataille is not superstitious about such things) for La Canatrice Chauve. The other side is painted red for La Leçon.

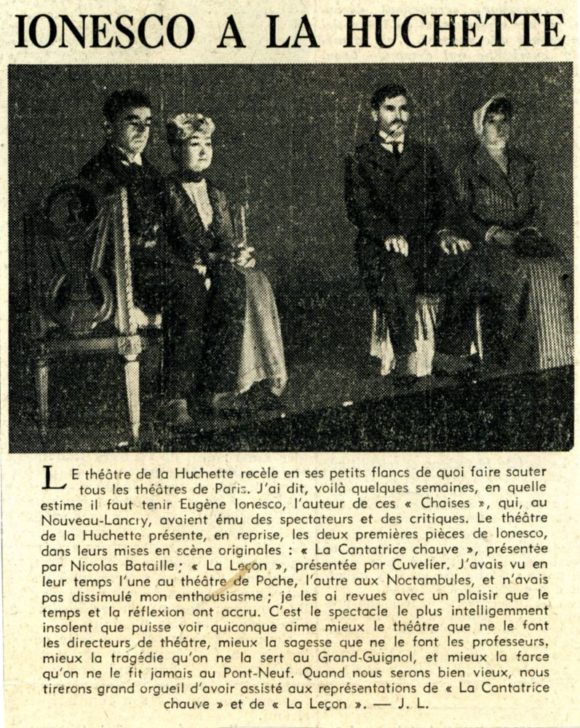

The dress rehearsal is October 7, 1952. A few days later Jacques Lemarchand will write in Le Figaro littéraire, “Within its small walls the Théâtre de la Huchette has what it takes to blow away all other Théâtres in Paris. (…) When we have grown old we will be proud to have attended performances of La Cantatrice Chauve and La Leçon.” This time around the Théâtre is full, however, after three months Ionesco’s first two plays must cede their place to others.

The revival

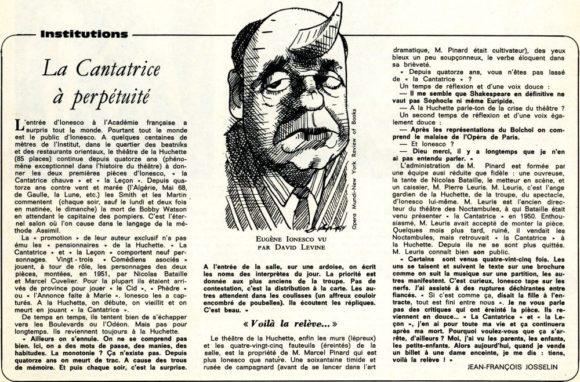

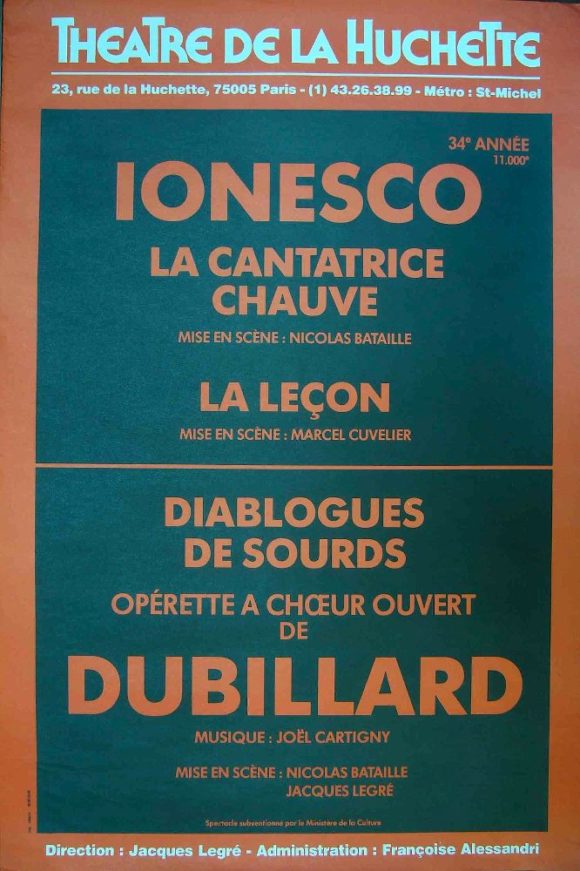

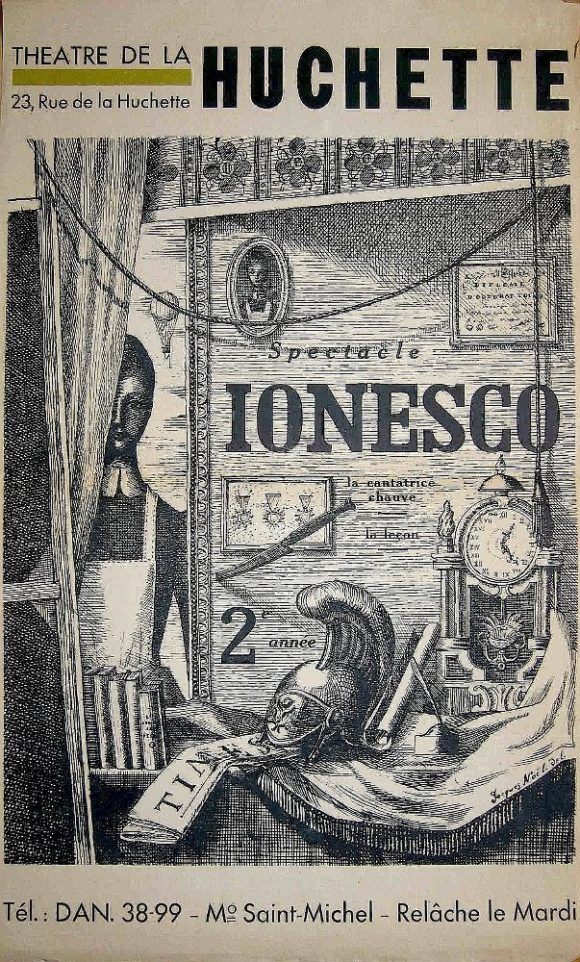

Since 1952 Nicolas Bataille and Marcel Cuvelier perform in or direct plays in the Théâtre de la Huchette. They often pass each other in the wings and share meals with their respective troupes. They eventually decide re-reunite the performances of La Cantatrice Chauve and La Leçon.

“We cannot restart the Ionesco Show without paying for some advertising!” declares Jacqueline Staup. “We have to put the odds in our favour."

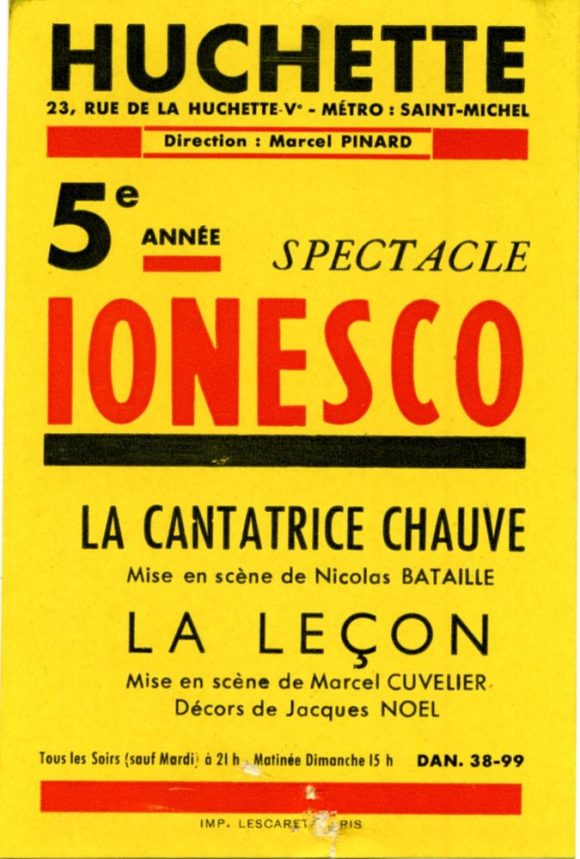

The only person able to lend them the necessary funds is her friend Louis Malle, a renowned French film director. He immediately accepts and lends the troupe one million francs (today’s equivalent of fifteen hundred euros), enough to pay the rent for the theatre and to promote the Ionesco Show that Marcel Pinard has accepted to renew from February 18 to March 18, 1957.

This time around it is an instant success.

Amazingly, the elite of Paris hurry to rue de la Huchette.

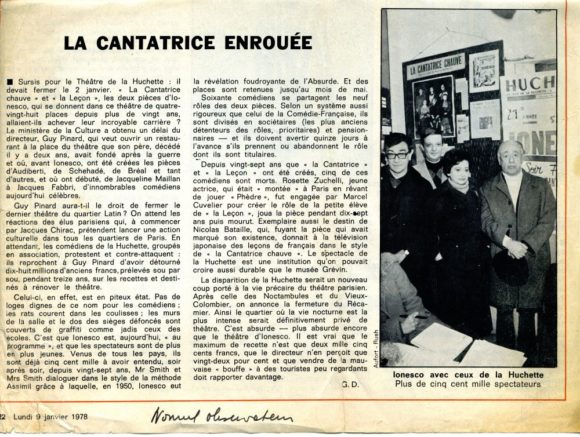

Until now too ahead of his time it appears that popularity has finally caught up with Ionesco. The likes of Edith Piaf, Sophia Loren, and Maurice Chevalier attend performances. This time around critics have nothing but praise for the plays. “La Cantatrice Chauve is seven years old,” writes Georges Lerminier. “She ages well, very well even. Not a single grey hair.” Truer words were never spoken. Presidents and even the Republics come and go but La Cantatrice Chauve and La Leçon endure. Though some spectators still leave the theatre dissatisfied, the public has now understood the meaning and the significance of these two plays.

Week after week, month after month, year after year, decade upon decade, the success never ends.

An avant-garde that became a classic

The Ionesco Show had such an impact that tours quickly followed one after the other.

Over the years the troupe travels across the globe from France to Germany, the United States, Lebanon, Japan, Tunisia, etc…

They inspire famous artists such as the photographer William Klein or the graphic designer Massin. Many prominent film directors such as Louis Malle, Robert Enrico, and Jacques Tati cast in their films actors from the Théâtre de la Huchette.

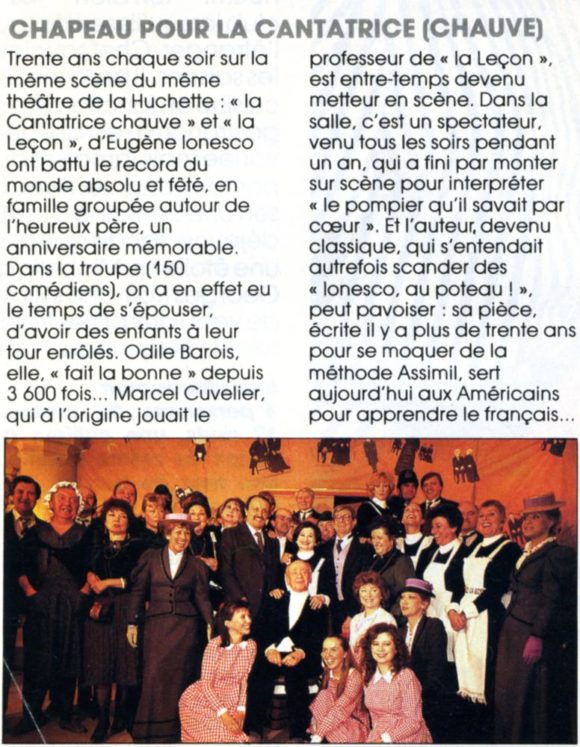

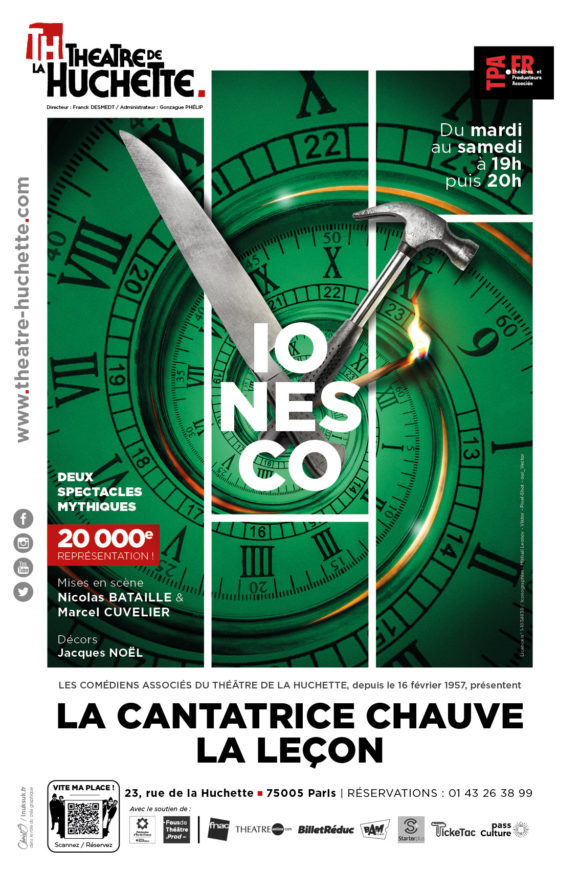

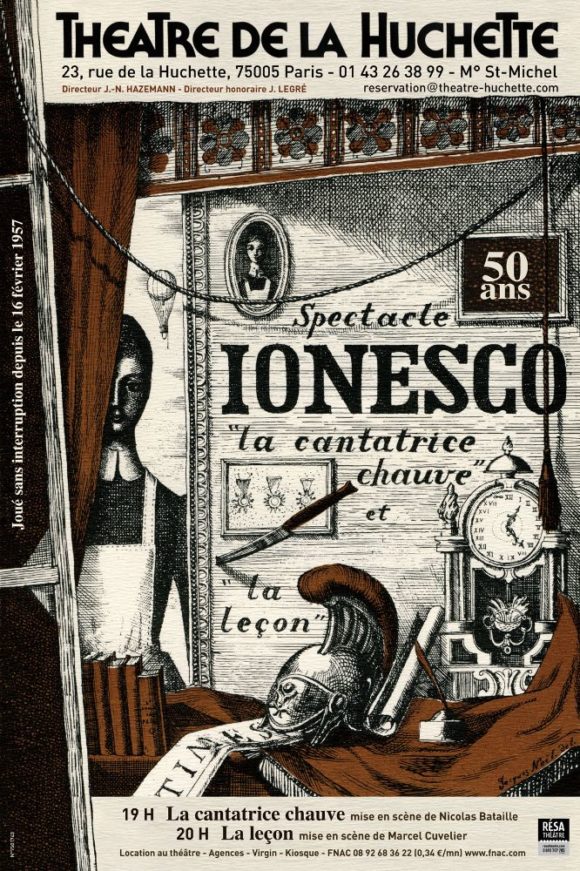

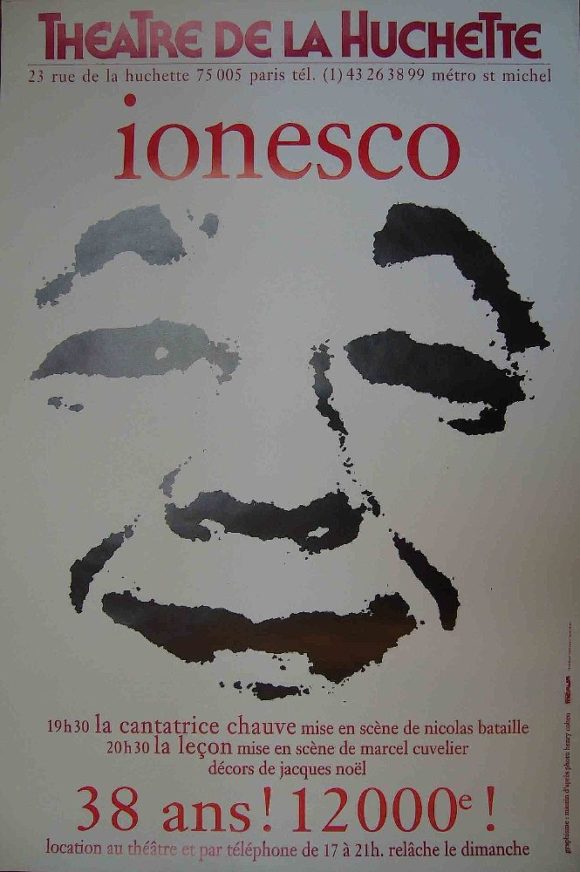

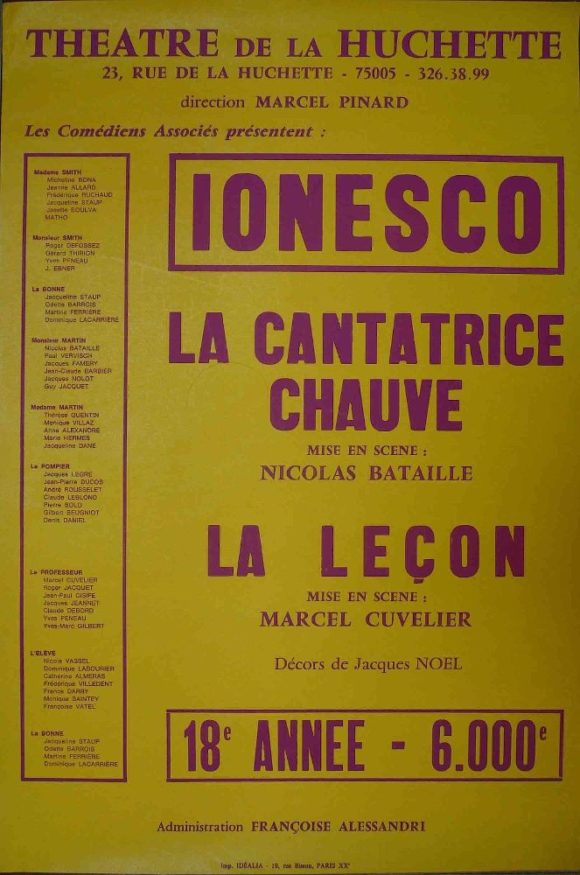

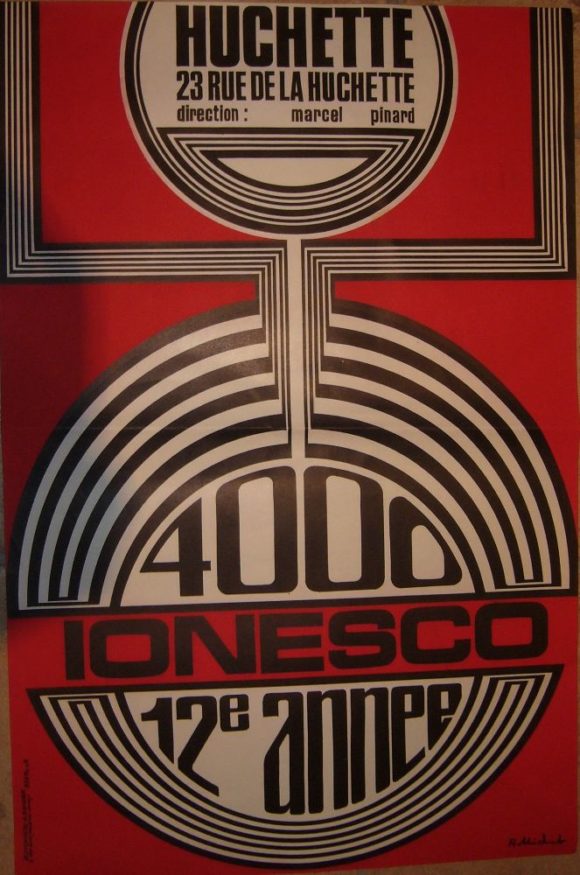

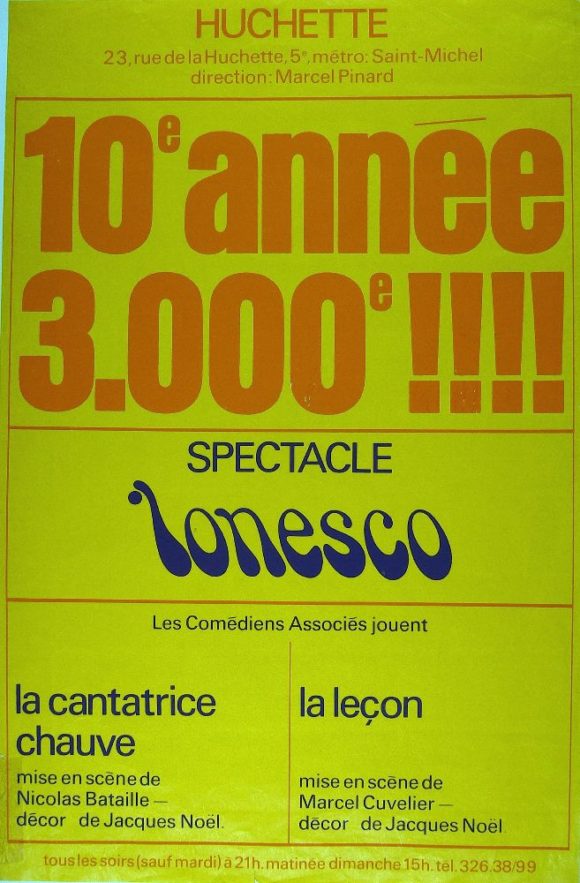

Now in its 65th year the Ionesco Show continues to hold the world record for the show that has been played non-stop in the same theatre.

More than 19,500 performances have been put on and watched by over 2 million spectators.

In 1996 the Ionesco Show was honored with the grande Medaille de Vermeil and in 2000 it received an honorary Moliere Award.